As HR professionals, we’re rightly cautious when someone tells us that they are “hiring for culture fit.” At its worst, hiring for culture fit is shorthand for “hiring people who like what I like and think how I think.” It suggests the worst kind of stereotype-based hiring with predictably grim outcomes for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). If you look around your team and everyone is the same age group, ethnicity, or gender, then a misdirected focus on “culture fit” may be the culprit.

It is important to recognize, however, that there is more than one way to think about culture fit. There are indeed some conceptions of fit that are quite exclusive (“only people like this fit here…”). But there are alternative conceptions of fit that are more inclusive (“how can we make sure we all fit here?”). In this blog post, I’ll explore the varying ways that we can think about fit, and how we can appropriately use the concept in our hiring.

Similarity Fit vs Complementary Fit

One way to think about fit is in terms of similarity. For example, if there are lots of people in a team who are extroverted, then only extroverts will fit in that team.

Sometimes this kind of thinking seems reasonable. If the job involves performing complex numerical calculations, then most of the people in the job will have good numerical skills, and your new hires will need good numerical skills too.

But a focus on fit as similarity can quickly turn negative if:

- It’s based on things that aren’t relevant to the job.

- It’s based on protected groups like age, ethnicity, or gender.

- It amplifies existing prejudices and biases.

- It’s stopping you from building a team with a diverse set of skills and perspectives.

Complementary fit is a different way to think about fit. Complementary fit exists when a need is filled or a gap is plugged, like a puzzle piece sliding into place. For example, a person who is good on details might fit well in a team populated by “big picture” types, because they fill a gap in that team.

Complementary fit also exists when what’s provided by the organization or the job matches what an employee is looking for in their ideal employer. For example, someone who is looking for career growth might fit better in an organization that promotes people rapidly than in an organization that emphasizes job security instead.

There’s a lot of reasons to hire for complementary fit rather than similarity fit. Research shows that people feel more committed and engaged at work when their needs are being met by what the organization provides (1). And thinking about fit in a complementary manner doesn’t carry the same DEI risks as thinking about fit in terms of similarity. When you’re looking for a match between what a person needs and what an organization provides, you’ll typically see that the organization provides many different things. For this reason, many different people end up fitting because they each find something that’s important to them in the organization. Complementary fit therefore represents an inclusive rather than an exclusive approach to fit.

Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow About Fit

Nobel-Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman describes two different modes or patterns of thinking in his bestselling book Thinking Fast and Slow (2).

System 1 thinking is automatic, instantaneous, and effortless. It happens with little conscious awareness, and it never turns off. When you’re hiring, it’s the kind of thinking that sums up an applicant in seconds based on how they look, how they walk and talk, where they grew up, and what their last job was. It’s the source of “gut feel” judgments about whether someone fits based on the most superficial of characteristics.

System 2 thinking is deliberate, focused, and effortful. Unlike System 1 thinking, System 2 needs to be deliberately engaged. In hiring, it’s the kind of thinking that weighs up the job requirements in comparison to the candidate. It’s responsible for thinking through scenarios and making a considered decision.

System 1 thinking is especially prone to matching based on similarity fit. It rapidly compares a candidate’s similarity to a stereotypical ideal and judges the candidate’s fit on that basis. As such, the DEI risks of hiring are amplified when System 1 is in charge. More complex thinking about complementary fit is the domain of System 2. This includes thinking about what a person adds to the team that’s not already there, and how the needs of the employee align with what’s provided by the organization.

So how do we give System 2 the best chance of taking the driver’s seat? It’s actually quite hard, because all too often System 2 is only engaged after System 1 has already supplied us with an answer. Even then, System 2 is often only used to find reasons to confirm or justify what System 1 has already decided!

My advice is:

- Suppress the information that System 1 loves: broad social category information like ethnicity, age, and gender, or even what their last job was.

- Supply System 2 with the information and data it loves: objective information on candidate skills, abilities, preferences, and needs, as well as information on the job requirements.

- Give yourself time and space to consider the information and make a sound decision.

- Think carefully about what you need before you start looking at candidates, and then objectively compare them to that requirement.

Fit With What?

The literature on alignment and culture fit is incredibly broad and encompasses a huge range of different things that a person can fit with:

- Fit with industry

- Fit with organization

- Fit with job / role

- Fit with team

Psychological research tends to show that the factors that impact people the most are the ones closest to them. So, your immediate supervisor has more impact on you than your director or CEO, your local work group has more impact on you than your division, and your organization has more impact than your industry.

When thinking about fit, in most cases it’s going to be better to focus on the lowest practical level. Managers and leaders come and go as do team members, which sometimes makes team fit too low-level to be practical. The job or role tends to be more stable, and is relatively close to the employee. Fit with the job and the role is therefore a prime focus, and the questions we can ask are:

- Does the candidate have the abilities, skills, and traits needed by the job?

- Are the candidate’s needs (e.g., for connection, salary, promotion, etc.) likely to be met in that job?

In those instances where people might change or move through jobs, such as in a future leader program or a graduate / campus hire program, it might be better to focus on fit with the organization:

- Does what the organization provide for employees align with what the employee is looking for from their ideal employer?

Tools to Help

At Criteria, we specialize in providing employers with the right tools to identify and hire the best employees. These tools can help you avoid a narrow focus on similarity fit, engage your System 2 with the right data, and address key requirements at the job, team, and organizational levels.

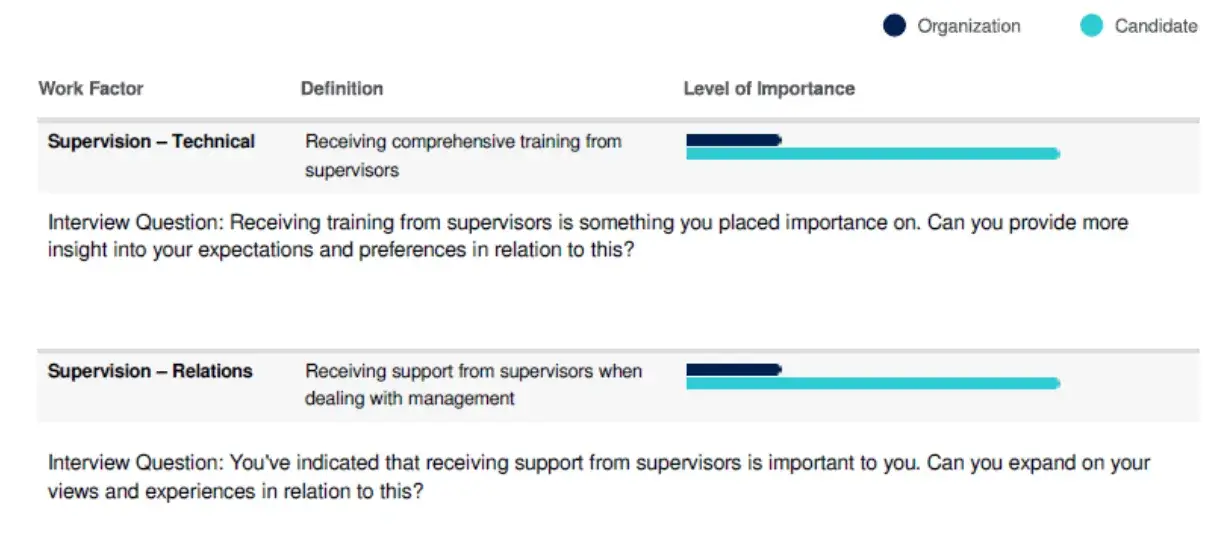

In particular, our Workplace Alignment Assessment (WAA) provides an objective method of calculating complementary culture fit (or alignment) between what the candidate is looking for from their ideal employer and what the organization provides.

The WAA report highlights those areas in which the employee and the organization are aligned, so you can easily see which needs or preferences have a good level of match.

In addition, the report also provides interview questions to help you explore, in a considered and thoughtful manner, any areas of potential misalignment.

As an example, you can see below that the candidate has said that two of their most important work factors are support from supervisors and getting training from supervisors. In this role / organization, however, these two things are not emphasized. The report for the WAA provides you with interview questions to better understand the implications of this possible misalignment.

Perhaps most importantly, an analysis of WAA responses from over 24,000 candidates shows that the assessment does not advantage some candidates over others in terms of their ethnicity, age, or gender. Due to its focus on complementary fit rather than similarity fit, and its assessment of fit across 20 different factors, the WAA can help you to promote DEI while also bringing in staff who are more likely to find what they are looking for at work.

Where to Go From Here

It is true that the concept of “fit” has baggage, and unwelcome baggage at that. At its worst, a focus on fit as similarity with existing staff or ideal prototypes can narrow the range of the people, perspectives, and abilities you bring into the business. The path forward is clearly different:

- Think about culture fit in terms of complementing one another, rather than similarity to one another. Aim for culture add, not just culture fit.

- Give yourself the information, time and opportunity to think objectively and deliberately, rather than subjectively and automatically.

- Use tools that promote a complementary focus on fit while providing you with the data to engage deliberate and focused thinking.

Keeping these tips in mind will help you to reap the benefits of alignment, such as better commitment and engagement and less turnover, while avoiding the traps of hiring like for like.

[1] Kristof-Brown, A. L., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: a meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58, 281-342.

[2] Kahenman, D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.